On Mahlaqa Bai, the first to give Urdu poetry a feminine voice

Every time I visit Hyderabad, I walk up the 500 steps leading to the shrine known as Koh-e-Ali or Maula Ali ka Pahad (the hill of my lord) to pray for strength to overcome difficulties or to offer my gratitude.  Like me, every year lakhs visit this shrine, which is dedicated to Ali ibn Abu Talib, the fourth Caliph of Islam and the first Imam of the Shia sect. He is called Mushkil Kusha, or the solver of difficulties.

Like me, every year lakhs visit this shrine, which is dedicated to Ali ibn Abu Talib, the fourth Caliph of Islam and the first Imam of the Shia sect. He is called Mushkil Kusha, or the solver of difficulties.

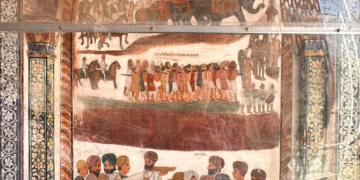

According to Tuzuk-e-Qutb Shahi, a eunuch in the court of Ibrahim Qutub Shah, the fourth ruler of the kingdom of Golconda, dreamt that a man dressed in green told him to visit a hill where Maula Ali was waiting for him. The eunuch went there in his dream and found Maula Ali on top of the hill with his hand resting on a stone. The next day, the eunuch went up the hill and saw a stone with an imprint of a hand. He got it hewn out of the rock and built a masonry arch over it. On hearing about this, Sultan Ibrahim Qutub Shah visited the hill and ordered a mosque to be built there. Since then, that area has been known as Koh-e-Ali. The rock with the hand imprint is enshrined at the back of the dargah. It is covered by a cloth and flowers and is said to have healing powers.

The poet-devotee

This year, on my visit to Koh-e-Ali, I went in search of another devotee of Maula Ali, a poet whose devotion was so deep that she ended nearly every verse with Ali’s name. She replaced the wooden canopy on the shrine and got a marble one made in its place.

Her name was Chanda (moon), and Asaf Jah II, the Nizam of Hyderabad, gave her the title Mahlaqa Bai (moon-faced lady). She was born in 1768 to Mida Bai, also known as Roop Kanwar Bai. Her birth was a miracle as her mother suffered a miscarriage while on a pilgrimage to Koh-e-Ali. Shah Tajalli Ali, a scholar and sage who was accompanying her, immediately brought her a thread and some incense sticks from the shrine. He tied the thread on her wrist and waved the incense under her nose. Roop Kanwar’s bleeding stopped and the foetus was safe.

Chanda Bibi went on to become one of the most important courtesans of the court of Asaf Jah II. She was extremely accomplished. Her teacher was the renowned exponent of khyal and dhrupad singing, Khush-hal Khan. She was also proficient at warfare and a consummate politician. She not only patronised poets and people of letters, but also rode to war dressed in male clothes with the Nizam. Though she may not be the first woman to have had her diwan published, as is popularly believed, she was the first to give Urdu poetry a feminine voice. Journalist Faiyaz Wajeeh tells me that it was Lutfun-Nisa of Bijapur’s diwan that came out a year before, in 1797. Lutfun-Nisa is overlooked because she wrote under the male sounding pen-name of Imteyaz.

In 1792, when her mother passed away, Mahlaqa Bai got a tomb made for her at the foot of Koh-e-Ali. She was buried next to her mother in 1824.

A plaque on the gateway of her tomb reads: Cypress of the garden of grace and rose tree of the grove of coquetry/ An ardent inamorata of Haider and supplicant of Panjetan/ When the glad tidings of the advent of death arrived from God/ She accepted it with her heart and heaven became her abode/ The voice of the invisible speaker called for her chronogram/ Alas! Mahlaqa of the Deccan departed for heaven 1240 AH (1824 AD).

Renovation efforts

Over the years, the garden where her tomb lies fell into disuse. No one knew that this was the resting place of a woman whom the Nizam had given the rank of an umara, and whose palanquin was preceded by drummers and 500 armed guards.

It was Scott Kugle, a professor of Emory University, who researched the life of Mahlaqa Bai and deduced that beneath this garden was her tomb. With the help of funds from the U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation and with supervision from the Centre for Deccan Studies, the tomb was renovated.

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/the-moon-faced-ladys-dargah/article23402810.ece